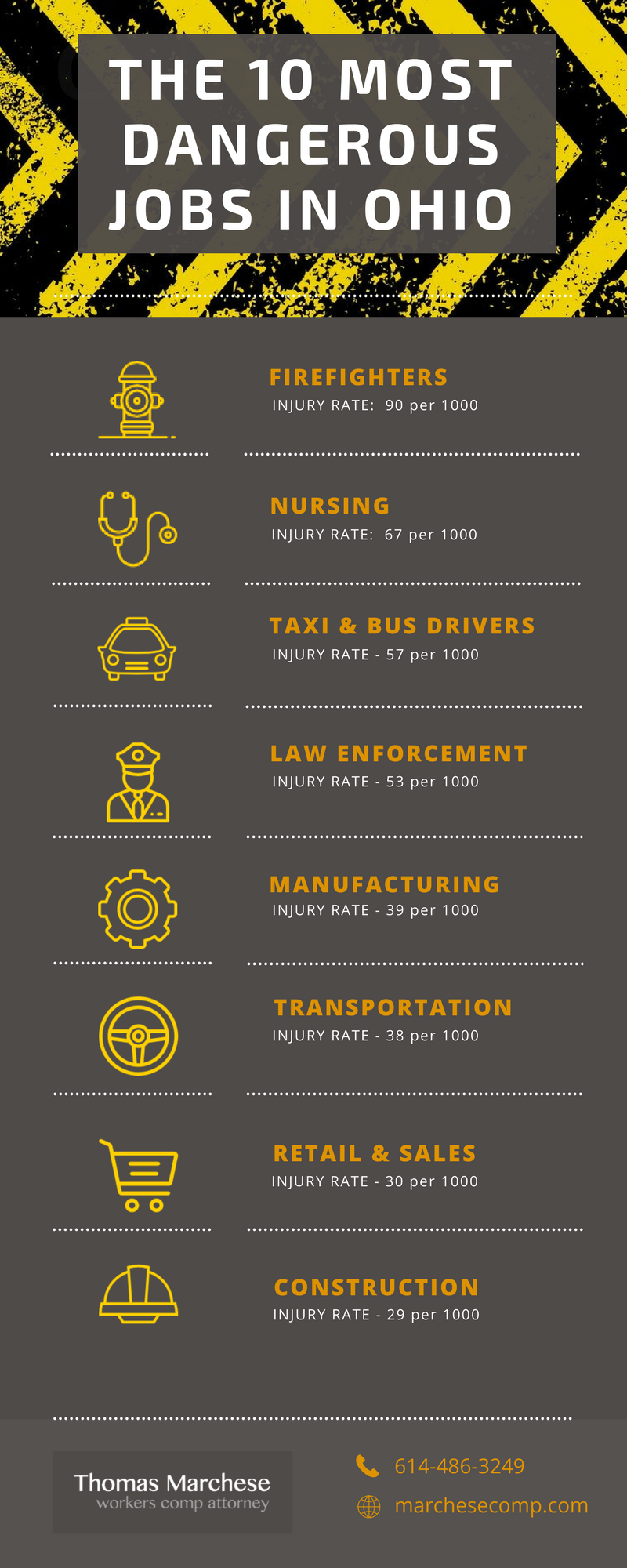

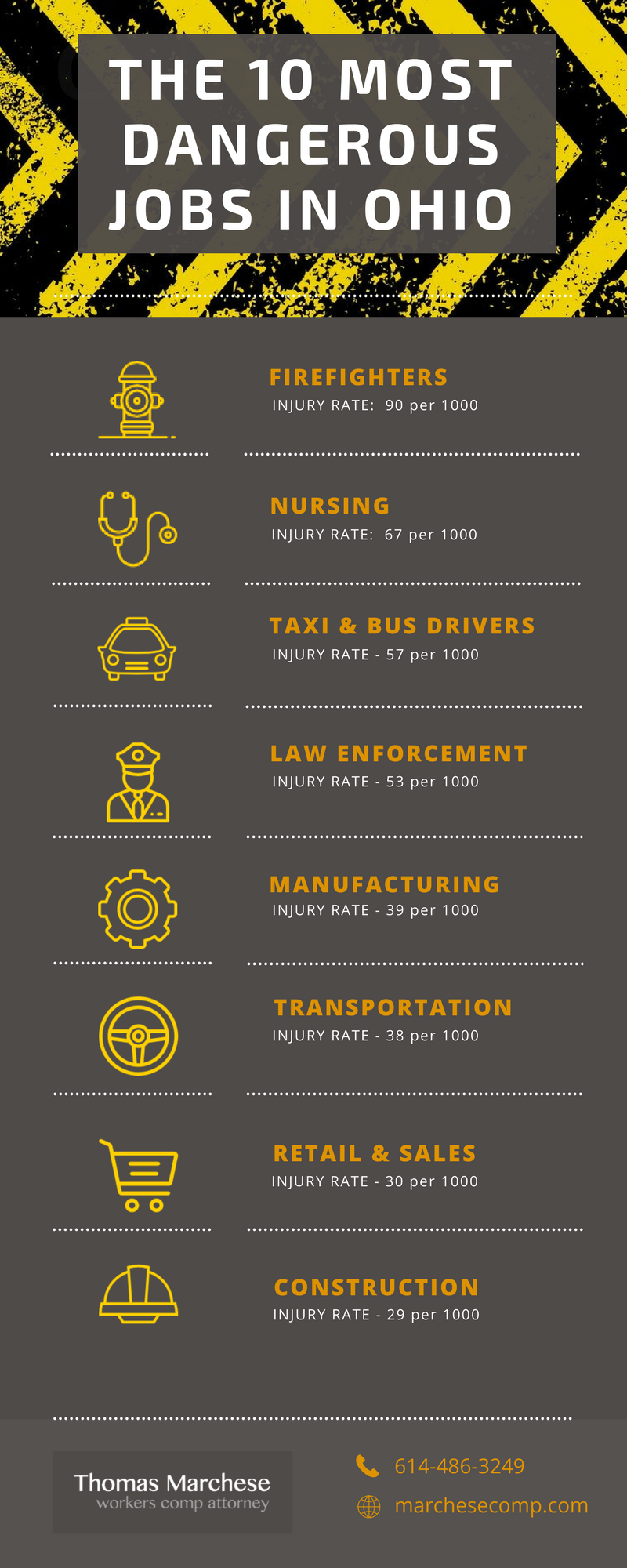

What are the 10 most dangerous occupations in Ohio?

The number of opioid-dependent injured workers in the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation system fell 19 percent in 2017. This is the sixth year in a row the numbers have fallen under the Bureau’s efforts to reduce opioid use and build a model pharmacy program.

On Thursday, Nick Trego, BWC Pharmacy Director told the agency’s board of directors that the number of injured workers who met or exceeded the threshold of being clinically dependent on opioids fell to 3,315 at the end of the fiscal year 2017. This is a 19 percent drop from 2016 and a 59 percent decrease since 2011.

“That means we have 4,714 fewer injured workers at risk for opioid addiction, overdose and death than we had in 2011,” Trego said, speaking before the board’s Medical Services and Safety committee. “These falling numbers are the direct result of our efforts to improve our protocols, more closely monitor our opioid population and encourage best practices from our prescribers. But we also have to give credit to the growing awareness of the opioid epidemic and efforts by the healthcare community, government and others to do something about it.”

Trego also told board members his department’s total drug costs fell to $86 million in 2017, $47 million less than in 2011. That includes $24 million less on opioids.

Working with addiction experts in 2011, the Bureau defined “clinically dependent” as a person who took at least 60 mg a day of morphine for 60 or more days. They found more than 8,000 injured workers who met or exceeded that threshold at the end of 2011, prompting several initiatives to reduce those numbers and improve the pharmacy operations.

Ensuing changes included the creation of a pharmacy and therapeutics committee, a panel of pharmacists and physicians that create and review the medication policy; the development of BWC’s first-ever formulary, and the 2016 Opioid Rule, which is now nationally recognized.

The rule holds prescribers accountable if they don’t follow best practices.

Trego told the board he expects the opioid numbers to continue to fall in the years ahead as prescription protocols evolve and alternative pain therapies emerge.

“Weaning a dependent person off opioids, or at least to safer levels, is a long, deliberate process requiring cooperation from the injured worker, health care providers, and the workers support network. We’re just one part of that equation, but we’re committed to it.” Trego said.

The Alaska Department of Labor last week repealed an old regulation that allowed employers to get an exemption to pay workers with disabilities less than the minimum wage if their disability limits their ability to get a job.

New Hampshire was the first state to repeal in 2015, followed by Maryland in 2016. Paying less than minimum wages to Americans with disabilities has been legal under federal law since 1938.

About 26 percent of Americans have mental or physical disabilities, and they are far less likely to work than the average American. Even so, 36 percent of Americans with disabilities had jobs in 2016 (among those who are working-age and not living in institutions), according to a recent report from the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire.

Advocates are pushing for services that focus on independence and integration over the isolation of mental institutions or segregated workshops. According to Robert Dinerstein, a law professor at American University and the director of the school’s Disability Rights Law Clinic, “There’s been a real sea change. There used to be such low expectations of what someone with Down’s syndrome could achieve.”

For most of modern American history, doctors and politicians didn’t really know what to do or how to help those born with severe developmental disabilities since the widespread assumption was that they could not learn, work, or care for themselves.

Sam Bagenstos, a disability rights attorney and University of Michigan law professor writes; “Children with significant disabilities received separate schooling, if they received schooling at all. As late as 1970, only a fifth of children with disabilities received public schooling; schools often simply excluded children with developmental disabilities as uneducable.

As they grew to adulthood, individuals with developmental disabilities moved to state-run institutions that theoretically provided training and treatment, but in practice warehoused them.”

Congress allowed business to pay them less than the minimum wage under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The law basically said a business could pay workers with disabilities as little as a few dollars an hour to do menial tasks in a “workshop” environment with other disabled workers. The idea was that low-paid work was better than not having the option to work at all.

During the civil rights era, advocates began pushing back against this paternalistic, custodial attitude, which led to a series of laws mandating equal access and equal treatment for Americans with disabilities.

The landmark Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 made it illegal for the first time for employers to discriminate against workers who with disabilities.

While these changes made huge strides in allowing Americans with disabilities to lead normal lives, they didn’t address the 1938 federal law that allows businesses to pay less than minimum wage in some cases.

States, such as Alaska, even passed their own laws to keep the practice in place.

In 1978, Alaska lawmakers amended the Wage and Hour Act to exempt businesses from paying minimum wage to “an individual whose earning capacity is impaired by physical or mental deficiency, age, or injury.”

As part of the law, employers had to apply for a state waiver showing that the worker’s mental or physical disability impairs their ability to do the job. Then the state labor commissioner decided whether that person would be unable to get a job that paid the minimum wage. It was a lengthy process, and it didn’t seem all that effective in creating new jobs.

Only six employers in Alaska claimed this exemption in 2016 and 2017, according to a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Labor. They include the Fairbanks Resource Agency, the Arc of Anchorage, Assets Inc., and Threshold Services, which all focus on training workers with disabilities to do tasks — such as recycling — in a sheltered setting.

Some of these organizations have embraced the sub-minimum wage ban, though the head of Threshold Services, a recycling nonprofit, told the Anchorage Daily News that she won’t be able to afford to pay all the workers minimum wage.

Jobs in segregated workplaces are exactly the kind that disability rights activists want to abolish — at least for the next generation of workers with disabilities, who now graduate from regular public schools and want to lead normal lives.

The workplace integration movement has pushed for “Employment First” initiatives in recent years, something many conservative and liberal states have adopted (Alaska did in 2014). These initiatives direct public service providers to focus on helping citizens with disabilities get regular jobs and live on their own, as opposed to more institutionalized care — getting a minimum wage job bagging groceries is considered far better than sorting recyclable trash in a sheltered environment with other workers with disabilities.

While the Employment First movement has picked up in recent years, it does pose new challenges in how providers should tailor job-training services for each person, says Dinerstein of American University.

One approach has been to give workers a job coach, who goes to work with them during their first month on the job and helps them learn the ropes.

People with disabilities just want a chance to be independent, taxpaying, productive members of society, says Dinerstein. “If we don’t do this, we are leaving them behind.”

We are not going to allow you to drain our state’s workers comp benefits.

House Representative Bill Seitz (R-Green Township) stated: “Every dollar that is spent on immigrants here illegally is a dollar that could be paid to a legal immigrant or citizen who is hurt at work.” Together with Rep. Larry Housholder (R-Glenford), they introduced Bill 380 (passed by the House) that would prevent illegal workers from collecting state workers compensation benefits if injured on the job. How much Ohio currently awards illegal immigrants is unclear because officials don’t ask about employee’s legal status.

In an interview with The Enquirer, Seitz said that immigrants working in Ohio illegally are not permitted to receive unemployment compensation, food stamps or Medicaid, except in emergency situations. Workers’ compensation shouldn’t be any different.

The proposal also permits the injured worker to sue his employer if he can prove that the employer knew the worker was here illegally.

According to Seitz, this adds some protection against unscrupulous employers who already face stiff federal fines for employing illegals. Representative Dan Ramos (D-Lorain) says that it is nearly impossible to prove that an employer knew workers were here illegally and it could be difficult to sue the employer from a foreign country if the worker is deported. “Workers compensation is a protection for the workers of Ohio,” Ramos said. “Like it or not, some Ohio industries rely on workers here illegally.

We shouldn’t have two sets of rules for workplace safety”. According to Pew Research Center, an estimated 8 million immigrants were working in the United States illegally in 2014. “These workers comprised about 26% of farming jobs and 16% of construction jobs. Those industries are where most work injuries are more likely”, Seitz said.

Some states allow immigrants working in the United States illegally to claim workers’ compensation while others do not. The National Conference of State Legislatures did not have a comprehensive list.

If the insurance company can prove that your injury was likely caused by your impaired judgement due to alcohol intoxication; you lose. Sometimes a person drinks the night before, then goes to work the next day less than 100%. Maybe you have one too many at an after work holiday party with co-workers who alert management after your injury occurs.

1. If your urine same or blood test show a blood alcohol concentration of .08 or higher at the time of injury, you are legally intoxicated and workers compensation claim can be denied.

2. When the insurance company suspects that you were alcohol-impaired but have no urine same or blood test to admit as evidence. They may have your co-workers testify that you were drunk on-the-job. An effective way to defeat this strategy is to have your co-workers write statements that they worked with you that day, that they observed you, and they believe you were acting normally and had full use of your mental and physical faculties. Armed with these written statements from your co-workers, the judge will examine the evidence and testimonials, then make a ruling.

3. If you are injured at work, immediately get an attorney who specializes in workers comp cases Your attorney may choose to get statements from your co-workers. The testimonials that they may provide could be critical to your success. As such, the insurance company will want to dissuade them for testifying. Let’s get started >